Scrotum.

Scrotum, scrotum, scrotum.

Go ahead—say it with me—scrotum.

There—that wasn’t so bad, was it?

I must say, the tempest in a teapot stirred up by the press over this issue these past two weeks says a lot more about the state of information dissemination in this country than anything else.

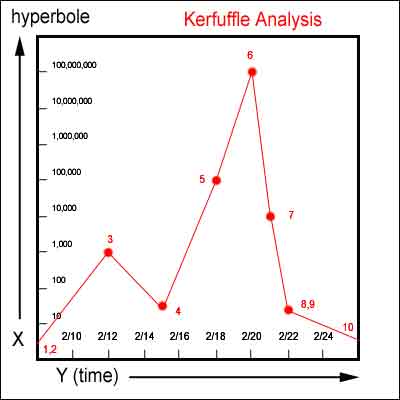

Here’s the anatomy of a kerfuffle:

1) An author (who also happens to be a public librarian) writes a quiet book about a smart and plucky girl who has a question about an anatomically correct word, and no adult to talk to about it because she has a tough home life

2) A prominent committee of librarians and acknowledged children’s literature experts, working on behalf of a venerable and respected association, picks this relatively unknown book for a major award

3) A group of librarians from various parts of the country debate the worthiness of the committee choice on a closed list serv, and a few get really uppity about a certain word choice

4) A publishing magazine of record takes note and reports on the word and the debate, taking care to talk to people on various sides of the issue (2/15)

5) A national paper of record notices said article, and publishes a less than thorough report on the issue on its front page, fanning the flames of controversy, and capturing the attention of televised media. Kerfuffle is in full swing (2/18)

6) Media talking heads and blogosphere chime in (2/20)

7) The same paper runs a short op-ed piece to balance the scale, bemoaning the crucifixion of “a sweet, funny book”, and throwing in references to The Music Man and Balzac. (2/21)

8 ) A publishing reporter for a national wire service decides to check up on the key players for a follow-up story about how the issue became a story in the first place, and finds inconsistency and hyperbole everywhere (2/22)

9) Embarrassed librarians backtrack

10) Much ado becomes nothing. Kerfuffle subsides

***

I think there are some important observations and lessons to take away from this whole soap opera.

I don’t know about you, but here’s what I’ve gleaned:

Words are powerful.

“Scrotum” is a powerful word.

So is the word “banned”.

In the case of the first word, Susan Patron knew it was powerful. That’s why she used it. It was a deliberate choice, and love it or not, there’s nothing innately wrong with using an anatomically correct word. In a great little interview broadcast Thursday on the CBC radio show As It Happens (part 1, at 14:30 min.), Patron explains her use of the word and her feelings about the controversy it has provoked. (Intentional on the first count, and unrepentant and levelheaded on the second.)

Her character Lucky is a girl whose mother has died, and whose father doesn’t want her. She is also a person who loves words and whose “brain was very complicated”, so that when she hears the word scrotum, she turns it over in her mind and puzzles over its meaning. Says Patron: “Her life is complicated, but it’s not all that different from the lives of so many kids growing up. They’re just really struggling to find out about the world.” A classic theme in children’s literature, and hardly the stuff of inflammatory tabloid writing, yet here we are with our undies in a bundle. It’s amazing the power one word has.

Talking frankly about body parts may make you uncomfortable. Clearly, it has made some librarians uncomfortable. But that has more to do with personal boundaries than any objective moral criteria. Where things get a little murky is when the person with the boundary issues is the gatekeeper for the community. All I can say is that I would rather have the book available and be able to make that choice for my own kid, instead of having someone make it for the whole community by keeping the book out of the library.

Which brings us to the second word, “banned”.

Also a powerful word, and used a little less responsibly this week.

When this story first broke in a pretty level-headed article in Publisher’s Weekly on 2/15, the gist was that Librarians were having some lively debate and strong feelings about the most recent Newbery winner. This is nothing new. Over the years there have been many MANY disagreements about whether a book chosen for the Newbery was the right book. History has also shown us that many past Newbery winners who may have not been the most obvious choice when they were picked have subsequently proved their brilliance. Madeline L’Engle’s classic A Wrinkle in Time, for example.

In fact my friend, the wise and incomparable Anita Silvey, made an excellent point in conversation this past week when she observed that this debate may have more to do with people’s opinions about the Newbery process than anything else, and scrotum was just a convenient peg to hang it on. (The last three Newbery winners have been criticized in certain circles for being a little obscure, and not to the taste of many young readers.)

I can’t help but notice with amusement that no one has objected to another passage in the first chapter of the book that involves a man “who had drunk half a gallon of rum listening to Johnny Cash all morning in his parked ’62 Cadillac, then fallen out of the car when he saw a rattlesnake on the passenger seat…” Apparently rum, drunkenness, and poor taste in automobiles have nothing on scrotums when it comes to getting people in a moral outrage. (I can’t criticize the Johnny Cash. I love Johnny Cash.)

However, putting aside people’s motivations for a moment, there is a big difference between lively debate, free expression of opinion, and banning a book.

This is something I would like to point out to Julie Bosman of the New York Times. In her FRONT PAGE article on 2/18 we see this statement: “The book has already been banned from school libraries in a handful of states in the South, the West and the Northeast, and librarians in other schools have indicated in the online debate that they may well follow suit.”

Them’s fighting words, alright.

No wonder the debate escalated to the TV talk-shows. Do a search this week for “banned book” and you’ll find repeated references to it all over the media, stemming from this one NYT piece.

That’s highly provocative, and in keeping with the overall inflammatory tone of the article. But here’s my question: who exactly is banning the book? Which states? Which libraries? “The South, the West and the Northeast” is a pretty large area. Give me names, details.

Well here’s the funny thing: in a subsequent discussion I had with AP publishing reporter Hillel Italie, who was gathering material for an article he put on the wire Thursday, he told me that when he went back an interviewed the librarians quoted in the original articles, he found no one who actually said they weren’t taking the book. The best he could do was to find some librarians who were still making up their mind, and for sure no one actually said they had “banned” the book. “Even Nilsson [one of the instigators of the whole thing, see below], who complained of the book’s ‘Howard Stern-type shock treatment,’ a reference to the lewd radio personality, told the AP that she is carrying it, although she questions whether it was worthy of a Newbery. Nilsson also said that she did not know of anyone who had refused to stock it.”

I’ll ask one more time….. who is banning this book?

The word “banned” is way too powerful a word for an organization like the New York Times to be throwing around. This is particularly true in a FRONT PAGE article that went to so little trouble to talk to the many authors, librarians, and other children’s book lovers who are defending the book. Indeed, there were some spicy rebuttals in the NYT editorial pages including one from a librarian quoted in the article who resented “being portrayed as pledging ‘to ban the book’”. She goes on to explain that libraries have limited resources, and that every library has to make choices about choosing books that best serve the community. She’s not interested in banning books, but that doesn’t mean she picks up every book that’s printed, even if it has a medal on the front. Coming from a very small town as I do, I know that that’s true.

So Ms. Bosman, say what you like about Patron, at least she knows why she’s choosing particular words, and is happy to explain it.

Read the entire book before offering an opinion

Do you think Larry King read this book? How about Barbara Walters? Hummm… yet they both had something to say about it this week, further fanning the flames in the mass media. I’m not even clear that many of the librarians who were chiming in this week, (and who were so prominently quoted in the press) had read the entire book. Afterall, the first appearance of scrotum comes on page 1. Those who felt incensed may not have read any further, even though the whole arc of the story rests on Lucky’s honest question about the meaning of the word.

The most egregious case of hyperbole on this front came from the aforementioned Dana Nilsson, a librarian from Durango, CO who seems to have been at the forefront of the critical wave against the book. Her original post on LM-Net, (and quoted prominently in the NYT piece), compared Patron to a shock-jock.

“‘This book included what I call a Howard Stern-type shock treatment just to see how far they could push the envelope, but they didn’t have the children in mind,’ Dana Nilsson, a teacher and librarian in Durango, Colo., wrote on LM_Net, a mailing list that reaches more than 16,000 school librarians. ‘How very sad.”’

Later on in my favorite quote of the article, and a masterpiece in ironic understatement, Nilsson goes on to say “‘I don’t want to start an issue about censorship,’ she said. ‘But you won’t find men’s genitalia in quality literature…At least not for children,’ she added.” For my part I would point her in the direction of Shakespeare and his codpieces, Brent Runyon’s brilliant The Burn Journals, and Gary Paulsen’s critically acclaimed and very funny Amazing Life of Birds among many others. (Check out this great list compiled by GELF magazine of other children’s books with scrotums specifically.)

A little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing, and it seems to me that Nilsson went on the record with her comments without taking time to thoroughly digest the story. Subsequently, the whole thing got away from her.

Apparently Patron agrees: “I’m sure that the person who wrote that did not finish reading the book. To be fair, if they had, they would understand that it was not at all used for shock value. It was very deliberately and carefully chosen, as a means for Lucky to…she is trying to grow up, she is trying to learn about the world …she is trying to get the tools she needs to survive emotionally in her little tiny town. And there is no one she can ask about what this word means so when [in a pivotal scene at the end of the book] she is finally able to ask her guardian the meaning of scrotum, the reader knows that we have come to a place of great trust. And that she has really found the parent that she can openly ask this question of, and get a truthful answer. Reading the whole book would give people the context they need.”

As far as I can tell, the only people involved in this whole thing who ACTUALLY read the whole book are the author, and the Newbery Committee.

My money’s on them.

What you say on a list serv may come back to bite you in the scrotum later

In this day and age, there is no such thing as a private conversation.

Especially if it involves a keyboard.

What’s new here isn’t the discussion or the controversy. As Kathleen Horning of The American Library Association’s ALSC division, (which awards the Newbery) correctly points out in Italie’s recent article “Librarians have these discussions all the time about books and ask each other, ‘How are you handling this situation'”.

This kind of debate has been happening for years anywhere that adults have to make decisions about what books to choose for children, be it in libraries, bookstores, or classrooms. There are children’s book review magazines, tradeshows, review databases, booklists, experts, and trade associations. People who work regularly with children’s books are constantly talking about the pros and cons of particular books. Everyone will have an opinion, they will all be different, and they will all be passionate.

What shifted here was that the debate leapt from the realm of private industry discussion to public discourse in the blink of an eye. I guarantee you that when those dissenting librarians made their posts to LM_Net, they weren’t expecting to be defending themselves in the New York Times.

Those of us who work in the children’s book industry have seen a tremendous shift take place with the rise of list servs, kid-lit blogs, and other electronic media. Where once there were a few established places that were the taste-makers on the subject of children’s books (like The Horn Book, Kirkus, School Library Journal, Publisher’s Weekly, and Booklist, to name a few), today everyone’s a critic. An established kid_lit blogger can be given the same weight as a print reviewer with 25 years experience—in some cases more weight, because an electronic review is so immediate—and a book can take off if a buzz starts on a list serv, even if no official media outlet has reviewed it yet.

What this also means is that the press is paying attention, and a handful of comments can quickly be perceived as a trend. Once the kerfuffle starts, there’s no controlling it. It’s like a wildfire in dry sagebrush.

***

So ultimately what’s the lesson here?

Should people be more aware that a private list serv isn’t really private? Probably.

Should we stop offering honest opinions about books in the quasi-public sector, even if sometimes we’re talking out of our butt? No.

Should children’s authors stop using sensitive words for fear of offending someone? Definitely not.

Should committees stop picking difficult books that challenge young readers, (and apparently some older readers too?) Hell no.

The most salient thing I’m taking away from this whole episode is a reminder about the importance of being thoughtful before offering an opinion, and to keep in mind that old adage about pride going before a fall.

Like my grandfather used to say, “Opinions are like ‘a**holes’; everyone’s got one.”

And at least half of us have scrotums, too.

_________________________________________________________

Postscript 2/26: Of course, controversy sells, and in the end Patron and Simon & Schuster will come out on top. Many thanks to A Fuse #8 Production for catching this upbeat and positive 2/24 LA Times article with hometown lucky-girl Patron. Higher Power indeed.

Ever the gentleman, Neil Gaiman has a great post on his blog about how he loves librarians unconditionally, but thinks perhaps some of these scrotum-decrying ones might have gone over to the dark side.

Also, for those of you inclined to walk the walk on this whole subject, head over to Bookshelves of Doom and grab one of Leila’s fabulous T’s, as featured this week on Gawker. You go, girl!

_________________________________________________________

Postscript 2/27: Check out this letter to the editor published in the 2/25 NYT from Kathleen Horning President of Association of Library Service to Children (ALSC), the division of ALA that awards the Newbery, and Cyndi Phillip, the President of the Association of School Librarians (AASL). Clearly these are the librarians Neil loves unconditionally, as we all should.

Also, head on over to From the Inside Out and check out the very wise guidelines for dealing with the press that Cyndi Phillip posted to LM_Net last week following the big dust-up. Many thanks to Liz B. at Pop Goes the Library for helping me find this.

_________________________________________________________

Postscript 2/28: The very last word in the dust-up comes straight from the author’s mouth in this life affirming LA Times article published yesterday. Apparently scrotum was, is, and will continue to be a children’s literary tool.

I now declare this kerfuffle finished.

26 comments

Comments feed for this article

February 24, 2007 at 11:45 am

Kelly

Awesome post! I’m linking to it now. And I have no idea why you weren’t on my blogroll. Adding…

February 24, 2007 at 12:39 pm

Susan

Yes, very good analysis, Kristen. Also, as I understand it, there was a step when an author from AS IF contacted Publishers Weekly about the anti-scrotum librarians on the library list-serv.

One of the reasons I started my blog two years ago was because I was interested in parents’ voices about choosing books to read at home. I was looking for an alternative to library, school, and book-review-page recommendations, all of which can be great, and so I started a blog. Since then, I’ve discovered many kindred spirits in the blogosphere.

When I began blogging, I culled the Internet for interesting features. I noticed right away that the world of children’s books reflected the culture wars. There was a campaign again the picture book “King and King,” in which a prince marries a prince. The “concerned parents” who wanted the book out of libraries and went straight to their legislators were obviously speaking from a script. It was depressing as all get-out.

Things do move at lightning-fast speed with the new technology. You are right to remind us, too, that there is no such thing as a private conversation these days.

February 24, 2007 at 1:31 pm

kmclean

Yes, author and AS IS champion Jordan Sonnenblick (who wrote Notes from a Midnight Driver, and Drums, Girls, and Dangerous Pie, two awesome books) read the posts on a digest of LM_net, and wrote to the electronic community-at-large to help rebut the argument. In PW’s original article, they did a great job of talking about all of the various sides of the debate, and I do think the debate was newsworthy in the children’s book community.

MY problem comes with the NYT article, and the subsequent dust-up. Like I said, a tempest in a national teapot.

February 24, 2007 at 5:07 pm

Little Willow

Great wrap-up and insight!

“Read the entire book before offering an opinion” — Yes, yes!

February 24, 2007 at 10:56 pm

MotherReader

Came here from Big A, and have to agree with Kelly, excellent post. Well presented, well thought out. Really enjoyed it.

February 24, 2007 at 11:44 pm

Elaine Anderson

Thanks for reasoning through this issue in such a thoughtful and thorough way.

February 25, 2007 at 9:17 am

jules

Oh thank you thank you for the well-written post — and the laughs. And now I am officially in love with your blog, having linked to it from Kelly’s post, and we’re totally addin’ you.

February 25, 2007 at 10:29 am

Jone

I enjoyed your post. Agree with you when you say: Read the entire book.

I loved the book and will have it in my library.

February 25, 2007 at 11:22 am

Liz B

Thank you!! I have blogged about your post at both Pop Goes the Library and at Tea Cozy. Absolutely note perfect.

February 25, 2007 at 11:25 am

Carolyn

I have this book in my library. I read it all, but didn’t think it was a Newbery winner.

I have put a 6-8 reading level sticker on it so my younger readers don’t take it out.

February 25, 2007 at 12:23 pm

Peter Milbury

Hello Kristen,

Thank you very much for your thorough examination of this little media tempest in a teapot. It is the best I have read thus far.

I especially like it that you have examined the mis-use and abuse of the “B word” by many who have used it in this context. Although I generally respect the NY Times for its depth andthoroughness, I was quite disappointed with their quality of writing and research for their articles and editorial in this instance.

Best wishes,

Peter Milbury, Moderator/Co-foinder of LM_NET

February 25, 2007 at 12:45 pm

Ronda Y.

Wow! Thank you, thank you and thank you AGAIN for a thoughtful, thought-provoking, and humorous take on this whole tempest/teapot. As someone who tends to suffer all to often from foot-in-mouth (i.e., open mouth-insert foot b/c of speaking before thinking), I especially appreciate the reminder as to the power of words.

February 25, 2007 at 3:30 pm

More Thoughts on a Higher Power « Bloggin’ BB

[…] Thoughts on the Great Scrotum Kerfuffle of 2007 […]

February 25, 2007 at 4:50 pm

Wendy Stoll

Ah, beautiful post! Wonderfully well-said!

I wondered, too, if people had actually read this book, or if they stopped the minute they read the word “scrotum” , and were too horrified to read on.

I bought “Lucky” as soon as it was announced…for MYSELF…to read, as I do any Newbery winner I have not yet read. I do this so I know what I’m ordering for my library, or not ordering, as the case may be. When I read the book I thought…eh, my kids won’t much like this, save it for middle school. I had not even noticed the word in question.

Now, “kerfuffle”: THERE’S a delicious word 🙂

Wendy Stoll

February 25, 2007 at 7:48 pm

totaltransformation

What would have happened if she called it a “man purse” instead? LOL.

February 25, 2007 at 8:00 pm

Jen Robinson

I enjoyed your post, too. These are issues that we all need to think about, as people who do regularly post opinions about books. Thanks for such a thoughtful and reasoned response.

February 26, 2007 at 3:26 pm

Sonja

Thank you for holding the NY Times to task for using the B-word. Librarians know that having a professional discussion about the merits of a particular book does not equal censorship, but I guess we didn’t realize that others would find this suspect.

February 27, 2007 at 12:50 am

Marta Ferguson

Hey Kristen,

Hilarious summary of the kerfuffle. Great to see another wordpress blog in the kidlitosphere.

;-)M

February 27, 2007 at 1:29 pm

Val

Thanks for a great post. I love the word kerfuffle it sums it all up so well!What a wonderful world it would be if critics and commentators read the whole book or watched the whole movie (actually invested some effort before commenting).

February 27, 2007 at 3:48 pm

Winnie McCarthy

Great post on this topic! I am sure most of the people complaining about the book hadn’t read it at all!

Thanks for linking to me!

March 16, 2007 at 9:12 am

Cheri Campbell

I found your marvelous summary while preparing for an in-house intellectual freedom workshop. Bravo!

This is a sample local-to-me, sadly knee-jerk reaction to the NYT article (published two days after the article, I should note) from a Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist who really should have known better:

http://www.cleveland.com/schultz/index.ssf?/base/living/1171974875176520.xml&coll=2

And a better article from another local paper:

http://www.chroniclet.com/2007_Archive/02-21-07/Daily%20Pages/022107head1.html

April 17, 2007 at 1:08 am

Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast » Blog Archive » Middle-Grade Books Round-Up, Part One(Including One Scrotastically Testacular Book)

[…] really addressed Scrotumgate (or what Kristen McLean at pixie stix kids pix aptly called “the Great Scrotum Kerfuffle of 2007“). So, in honor of speaking out against those adults who feel “discomfort . . . {about} […]

February 22, 2012 at 12:02 pm

My Newberry Challenge Update for February « Deliberate Obfuscation

[…] Something about the author: Susan Patron is a retired Los Angeles librarian who wrote her first book in 1990. When Lucky was awarded the Newberry, there was much controversy over her use of the word “scrotum” in the book’s first pages. The context of the word was as part of a story about a dog getting bit in said place by a rattlesnake. About the controversy, Patron said that she took the event from a real life story, and that the use of the word was intentional. […]

April 3, 2012 at 6:26 am

Scrotum pix | Dogcollarpetsa

[…] Thoughts on the Great Scrotum Kerfuffle of 2007 « pixie stix kids pixFeb 24, 2007 … Thoughts, Observations, and Ideas About Children’s Books. […]

May 18, 2013 at 9:01 pm

Leah Grose

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different browsers and both show the same outcome.Katy Home Security, 4410 Huntwood Hills Ln., Katy, TX 77494 – (281) 394-0477

July 9, 2013 at 5:17 am

www.rpasarchitect.com

I have been exploring for a little for any high quality articles or blog posts in this kind of house .

Exploring in Yahoo I ultimately stumbled upon this web

site. Reading this info So i’m satisfied to exhibit that I’ve an

incredibly excellent uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I

needed. I most without a doubt will make certain to do not overlook this website and give it a glance

on a relentless basis.